‘Let’s choose executors and talk of wills,’ King Richard commands in Richard II. Richard quickly follows this command with a question: ‘And yet not so, for what can we bequeath save our deposed bodies to the ground?’ Whether comedic, tragic, or historical, Shakespeare’s plays return to the idea behind Richard’s question: to thoughts on wills and inheritance.

The Merchant of Venice looks at the power of the final words of a dead father, but plays like King Lear ask: what happens if the heirs inherit while the benefactor still lives? And likewise, Richard II and Richard III dive into the corruption of monarchs, raising questions about the meaning of inheritance, about whether inheritance is something bequeathed or something taken.

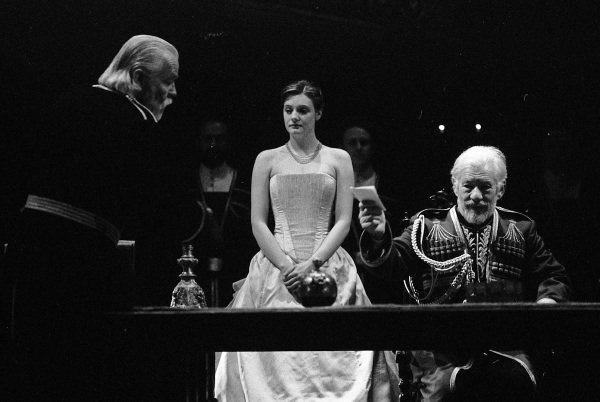

In the Merchant of Venice, Portia stands as a wealthy heiress to her deceased father. But, the catch: she has no choice of husband. Rather, her father’s will outlines a competition of wit for any potential suitors, a tool allowing her father to control her love life and future from beyond the grave. Portia is disgruntled about this stifling inheritance and complains that her ‘will’ has been ‘curbed by the will of a dead father.’

Like Portia, other daughters from Shakespeare find themselves swayed by the will of a mercurial father, the living driven by the desires of the dead or dying. King Lear opens with a bizarre display as the king instructs his three daughters to speak their love for him in order to inherit the largest part of his newly divided kingdom. From a Renaissance perspective, the splitting of a kingdom would be enough to alarm an audience. But the division of land isn’t even the most shocking part of the scene; rather, the shock is Lear’s decision to implement his will immediately so that he might ‘unburthen’d crawl toward death.’

King Lear replaces the dead father match-making from his grave with an aged, but living, father who seeks to pass off a kingdom to his daughters while hovering over their shoulders. Dead father or not, all the daughters find themselves unwilling pawns playing by the rules of their parents. Yet, whereas the will of Portia’s father leads her to a happy marriage with Lord Antonio, King Lear’s will pushes his two elder daughters to wicked scheming and his youngest daughter into exile before all five characters come to miserable ends.

However, the most unsanctioned inheritors appear not in fictional plays, but in the histories. A duel at the beginning of Richard II allows King Richard to exile Henry Bolingbroke. With the exile, Richard orchestrates a seemingly legal means to rob Henry of his rightful inheritance as the son of the wealthy and dying John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster.

Of course, Richard II’s plans backfire when Henry Bolingbroke returns to England, claiming himself a different man than the one he left; Henry makes a point that he was exiled as the Duke of Hereford, but has since become the Duke of Lancaster following his father’s death. The distinction of an inherited title allows Henry to return to England and gather the forces to depose Richard.

In Richard III, Shakespeare explores a comparable, brand of inheritance to Richard II. Within the first speech of the play, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, has already declared that he ‘of Edward’s heirs the murderer shall be.’ Richard III acts beyond the law, killing off the rightful inheritors so that he can steal the crown. And Richard III’s course of action leads him into a similar predicament as the previous Richard: displaced by a Henry – this time Henry VII, father of Henry VIII.

Both history plays investigate inheritance from a position of action, from a place where the would-be heir takes the reins of power into his own hands without the sanctity of law. Both Richards seek power and wealth of which they have no rightful claim. And both Henrys depose their kings and take the throne themselves in the name of justice, as a way to stunt a corrupted line of inheritance.

Playing with kingdoms might hold greater weight than the choice of husband, but whether a play ends in marriage or murder, Shakespeare’s drama looks at inheritance as a lens into human morality, a lens that magnifies questions about the meaning of inheritance and the obligations of an heir.